There are

many films starring Audrey Hepburn, and sadly I won’t talk about them all. Some

retain some grace despite their lack of good directing (Breakfast at Tiffany’s) or casting mistakes (Sabrina, My Fair Lady, War and Peace). Hepburn, always perfect,

is the light that pervades and that makes these films classics that will be

remembered. Among these flawed films, one of them is particularly endearing.

Though time has taken its toll on Mel Ferrer’s Green Mansions (1959), the picture remains charming to watch.

Seeing Hepburn through the eyes of her husband triggers some emotion. But, most

of all, this film has brought us Bob Willoughby’s best work. The famous

photographer has immortalized Audrey in the role of Rima, a young girl living

in the forest in complete harmony with nature. These photographs are amongst

the most beautiful taken of Audrey, the light illuminating her Madonna-like

face, her slender body blending into the landscape. This film is also the

occasion to see Hepburn acting with one of the greatest actors of her

generation, Anthony Perkins. Romantic as ever, Perkins is perfectly suited for

the part of Abel, and their love scenes together are enough to make the movie

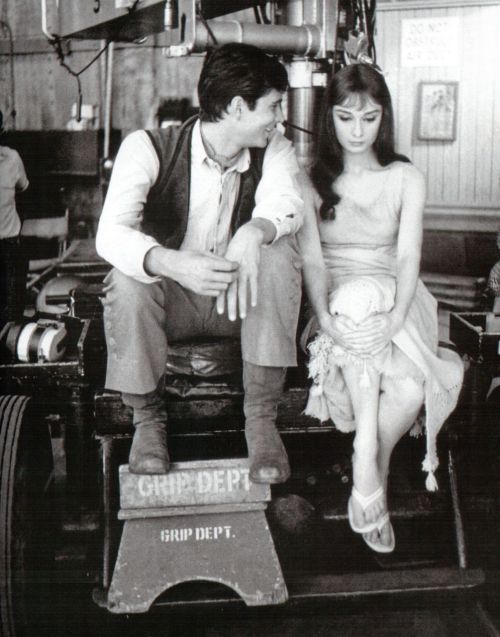

interesting. Willoughby captured the great relationship that existed between the

two actors, twins in loneliness, fragility and poetry.

|

| Audrey Hepburn in Green Mansions, photograph by Bob Willoughby |

|

| Anthony Perkins and Audrey Hepburn on the shooting of Green Mansions, photograph by Bob Willoughby |

In this

final part of my comments on Hepburn’s films I would like to mention two dark

films, which place Hepburn in the position of a victim, subjected and prone to

violence.

A VICTIM OF LOVE

One of the many reasons I love

Audrey Hepburn so much is that she appeared to be devoid of aggressiveness or

violence. Yet these two films place her in that position, and the result is

strangely awkward, in a very poetic way.

THE UNFORGIVEN

(1960) by John Huston

Hepburn dazzles as Rachel Zachary,

youngest of a family of three brothers and a widowed mother (the eternal

Lillian Gish). The love that binds the family together is shaken by allegations

that Rachel was stolen from an Indian tribe and that, as she is not white, she

belongs with her own kind. Rachel is thus subjected to the violence of her

racist neighbors, to the violence of Indians who come to reclaim her, to the

rejection of one of her brothers, and to her own distress when she discovers

the truth. All this will lead her to an incredible act of violence: the killing

of her biological brother. The scene is startling as the act is done without

hatred; Hepburn, it seems, cannot hate, and if her character kills, it is out

of a necessity for survival. Rachel must remain with her real family, the one

that raised her, loved her through the years. Lillian Gish delivers a

heartbreaking performance as the strong (and yet so fragile) mother of the

Zacharys. Burt Lancaster plays the elder brother, the one with whom Rachel

entertains a troubling relationship. The two obviously love each other with

more than brotherly love and that is the most disturbing aspect of the story.

The revelation of Rachel’s true origins allows them to become what brotherhood

forbids: lovers. This ending makes of the film a strange object, filled with a

strong view against racism, arguing that love is what defines a family, not

blood, and yet denies that argument by having the two stars married at the end.

It is possible that this ending was required at the time, when having two

majors stars in the same film demanded a love story between them. That is where

the writers and the producers made their mistake: the film was not about that

sort of love. It dealt with a much bigger issue: the eternal and unbreakable

love created in the family unit.

|

| Burt Lancaster and Audrey Hepburn in The Unforgiven |

Hepburn delivers a magnificent

performance, filled with angst and confusion. During the extremely violent

confrontation with the neighbors, Hepburn appears as a small bird, a perfect

prey for the hating wolves that surround her. Her most glorious scene, she

performs alone. Rachel is in her bedroom after finding out the truth. And

bluntly, without looking away, she paints herself as an Indian would. Rachel’s

first act of violence is against herself.

ROBIN AND MARIAN (1976) by Richard Lester

After a nine-year break, Audrey

Hepburn returned for this magnificent picture. An aging Robin returns form the

Crusades and finds that his longtime love, Maid Marian, has become an abbess in

a priory. The reunion is difficult after the passing of so many years. Marian

resents Robin for choosing his king over her, and Robin, despite his elder

years, is still the same restless and impetuous man he was. Trouble arrives

with Robin’s old foe, the Sheriff of Nottingham. The film is filled with

melancholy as it reflects on a love that hasn’t had enough time to live and on the

inescapable workings of Time on humankind. Hepburn builds a Marian that is

strong in her beliefs, her love and resolutions. More than ever, her body suggests

a woman in dire need of protection. In a touching scene, Marian reveals to

Robin that she tried to end her life when he left. Hepburn doesn’t give into an

easy pathos, she delivers her lines in a disarmingly natural way, thus

remaining true to the chaste and modest nature of her character. And it is her

character that prevails above her flesh, for in the end, it is Robin who needs help.

Badly wounded, Robin, still blind to his own mortality, convinced of his

legendary nature, believes he can live. The clear-sighted Marian knows that all

life comes to an end. So, help she provides, in the most daring and violent

manner. Thus, in the fashion of tragic lovers, Robin and Marian die together,

poisoned by her hand. Here again, violence is exerted and diverted, as it is a

gentle one. To explain her gesture, Marian delivers a beautiful and poignant

speech: “I love you. More than all you know. I love you more than children.

More than fields I’ve planted with my hands. I love you more than morning

prayers or peace or food to eat. I love you more than sunlight, more than flesh

or joy, or one more day. I love you… more than God.”

.jpg) |

| Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn in Robin and Marian |

“A thing of

beauty is a joy forever” wrote John Keats in Endymion. “Its loveliness

increases; it will never pass into nothingness”. Words that apply all too well to the

exceptional Audrey Hepburn, whose filmography will forever remain like “an

endless fountain of immortal drink, Pouring unto us from the heaven’s brink.”

Viddy Well.

E.C

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire